August: Guarding the Door to the West

From 1958 until 1961, the Soviet Union and the U.S. held multiple diplomatic engagements to solve the Berlin question. The U.S. was convinced that if they were to remove their garrisons from West Berlin, the city would soon fall under communist influence. Under pressure from the GDR, and unhappy with a capitalist city thriving 90 miles behind the Iron Curtain, the Soviets continued to push for the removal of western garrisons and the unification of the city under communist rule.

Following the Soviet ultimatum in November 1958, the U.S., Great Britain, and France established the LIVE OAK contingency planning staff, collocated with U.S. European Command (USEUCOM) in Paris, France, to develop military responses to possible Soviet restrictions on Allied access to West Berlin. Air Force General Lauris Norstad, the USEUCOM commander at the time, donned a third hat as the LIVE OAK commander in addition to his role as the NATO Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR). The command also integrated LIVE OAK planning into its theater mission.

General Norstad quickly recognized the untenable situation of the Allies. The only military courses of action if the Soviets chose to isolate West Berlin was evacuation of the city, enduring a siege, or conducting a forcible entry from West Germany. Not only were troop levels in Europe insufficient for the latter option, but military action of that magnitude would likely escalate to a nuclear conflict. The only viable military option was sending armed probes to test Soviet resolve, while having a corps-size force on standby to rescue the probe in the event the Soviets or East Germans held their ground.

Following the failed summit between U.S. President Kennedy and Khrushchev in Vienna, Austria in June 1961, the U.S. moved LIVE OAK to Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE) in Rocquencourt, France. While still only manned by American, British, French personnel, the U.S. intended to synchronize the Berlin contingency planning with NATO contingency planning by moving LIVE OAK to SHAPE. The move also helped support the U.S. request that Allied nations improve and increase their conventional war fighting capabilities. When Berlin contingency plans were shared with NATO allies, they saw the detailed tables of land, sea, and air forces required for each NATO member - a not-so-subtle way of communicating force requirements.

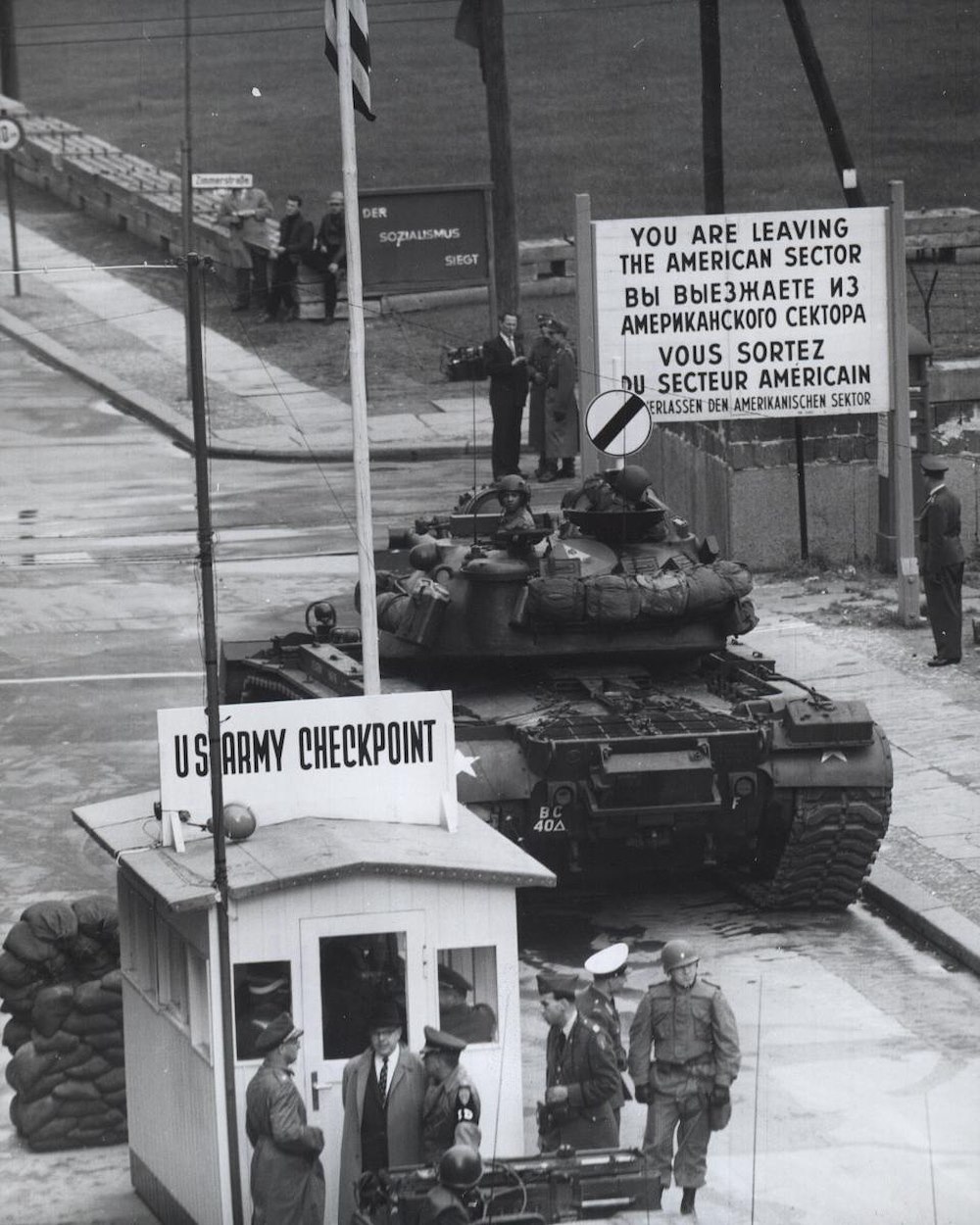

Over the next few months minor confrontations flared on both sides as the East German border guards imposed ever increasing restrictions to passage between East and West Berlin. On several occasions, U.S. and Soviet armored vehicles faced off across border crossing points such as Checkpoint Charlie. By the end of 1961, both sides had moderated their military activities along the border and a tenuous calm had fallen over the city. Despite this, the Berlin Wall became a controversial symbol and frequent flashpoint in the continued Cold War confrontation with the Soviets.